Dopesick: A Story In Three Parts

A limited series by Hulu, a book by Beth Macy, an illness I know.

It’s taken me about two months to write this, because I first tried to write it as one very long newsletter, and then had to cut out lots of important stuff. Then I got stuck in the treacle soup, afloat and in despair about the damning information I kept finding out. Then my own personal relation to it felt too much. So this has been a slow burn, and it’ll be a slow burn for you too. I’m going to break this down into three parts for you: for ease of reading.

Content warning: Frank discussion of illicit drug use, overdose, and death.

First of all, I want to give you some context about what opiates are, and how they have caused multiple addiction epidemics over the years, and how we went from seeing opiate addiction as a medical disease to a criminal problem. This is what I’ll launch into today.

Next I want to carry you through the humanity of it all, the shame, the stigma, the heartbreak, the sickness that crawls into your bones and brain: a termite burrowing deep into your foundations, gnawing at you from the inside out, hanging you out to dry.

I want to finish on a more hopeful note: what we know works, how we recover, the way upward and onward and into the light, how to love a person at their most unloveable, how the disease of addiction endures but so too does love.

I’ll publish these three parts over the next week - the first part won’t be paywalled, but the last two will be, so that I can talk a little more honestly and vulnerably.

Part One: The history

In a nutshell the book and series Dopesick is a telling of how the opioid crisis ripped through the United States, peddled and funded by Purdue Pharma, and devastated the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans - most of them the working poor. The series doesn’t give a hugely in depth overview of the history of opiate drugs in the world, but Beth Macy’s book does, and I’ve gathered some supplemental information for context to help wrap your head around how this drug, this god given nectar of nature, has destroyed so much and so many over the centuries.

Opium is a dried latex substance from the seed capsules of opium poppies, and was discovered and rediscovered over and over again throughout ancient times and into the enlightenment. The first documented cultivation of the opium poppy was around 3400 BC in Mesopotamia, where it was known as “the joy plant.” It was used by the Egyptians and Greeks, combined with Hemlock in order for people to die by suicide, or be euthanised. In Greek mythology the gods Hypnos (sleep), Nyx (night), and Thanatos (death) are pictured adorned in poppies. Opium in ancient times was a potion used for “visionary glimpses of a future happiness,” when that happiness did not come, and if the opium ran out, its users “would die without it.” So it still goes today.

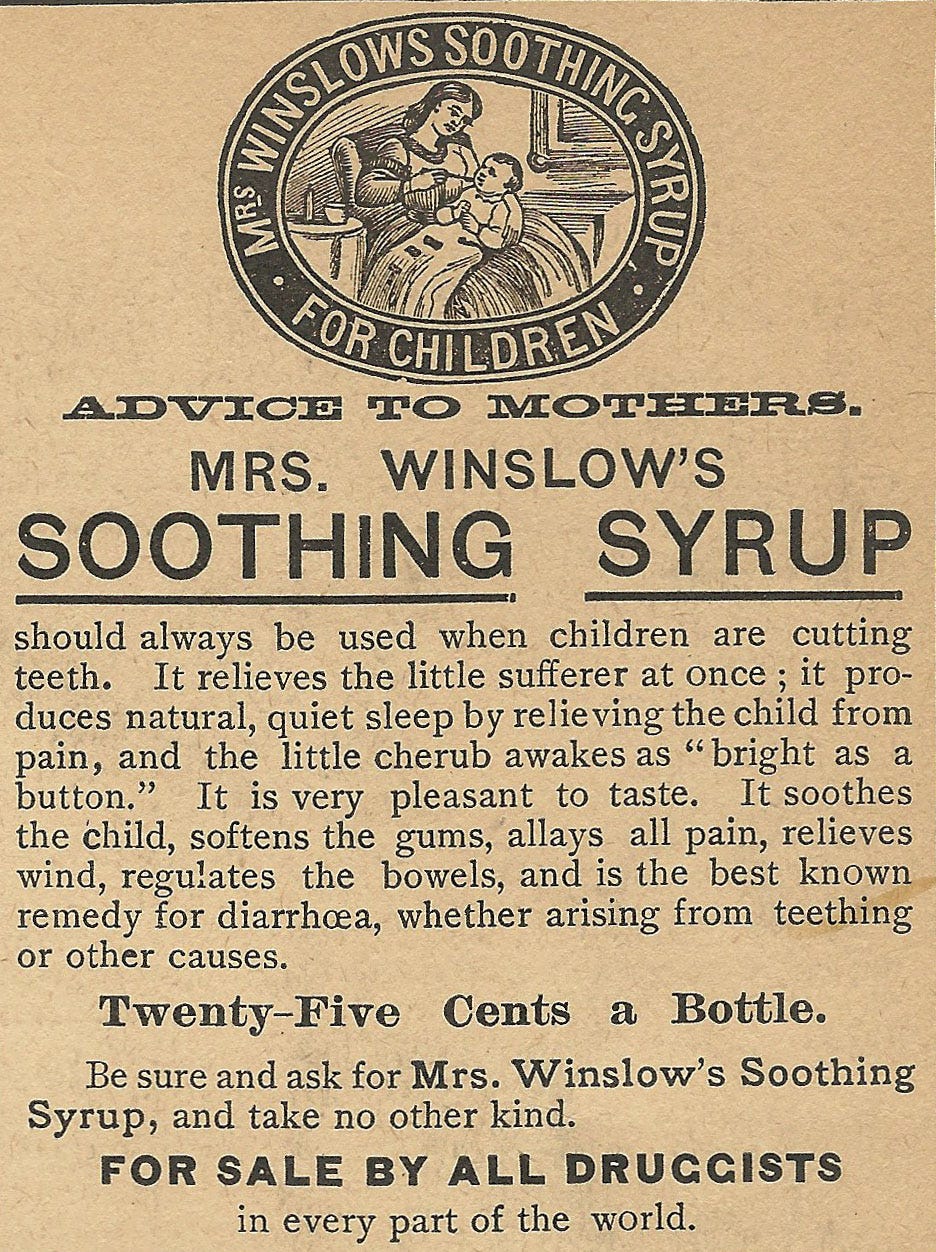

A huge amount of opium poppies are grown in the middle east, and between 500-1500 AD opium was used by doctors for anaesthesia, and to treat melancholy. Around 700 AD it was introduced to China, and India for similar purposes, and it was used for recreational purposes across Asia and the middle east over the next 800 years, with varying ups and downs in supply and demand. Around 1500 AD it became more commonplace in western medicine: In the late 16th century laudanum was the opiate mixture of choice (tincture of opium combined with ethanol, essentially, alcohol and heroin), and was seen as a cure-all. Dr Thomas Sydenham (often referred to as the “English Hippocrates” or the “father of western medicine”) was known for saying “among the remedies which it has pleased Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium.” Opium kind of was a cure all: it worked surprisingly well for a lot of issues plaguing general populations at the time: its constipating effects working as treatment for diseases like cholera and dysentery, it’s cough suppressant properties treating tuberculosis, and medical textbooks declared it useful for healthy populations to "optimize the internal equilibrium of the human body."

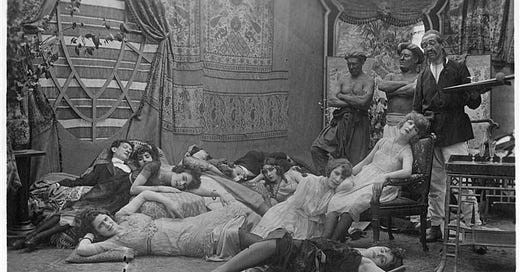

Opium was popular for injecting amongst the upper class in Europe in the late 1800’s, and was used to treat battle injuries in the Civil War in the US - an estimated 100,000 soldiers developed addiction. As these soldiers returned from war they developed a strange disease involving mental distress, vomiting and diarrhea, delusions, and insomnia. This became known as “soldier’s disease,” and it was found to be treatable with morphine. Soldier’s disease was of course, withdrawal, or dopesickness. Around this time a pharmacist working for drug company Bayer discovered Diacetylmorphine - aka Heroin. Heroin was twice as strong as morphine, morphine was twice as strong as opium, and Bayer believed that Heroin’s respiratory depressant and cough suppressant effects were a sure cure for tuberculosis that was at the time ravishing the west. Bayer also declared it would be a cure for alcoholism and morphine abuse, declaring it a non-addictive alternative to morphine (remember this, we’ll be here again). It was so popular at the turn of the 20th century that it was used for babies with hiccups, menstrual cramps, and joint pain. Daily opium users were not socially stigmatised, because their addiction was prescribed to them by doctors - by 1900 around 1 in 200 people in the global north were addicted to some form of opium. While opiate addiction got landed with the name “soldier’s disease,” and it was seen as a dependence born by war heroes (thus the name Heroin, as it made them more heroic in battle by masking their pain), it was used so frequently to treat menstrual pain and “hysteria,” that in this time two thirds of opiate addicts were women.

Opiate addicts went around with little pouches hanging around their neck, supplied by their family doctors: in these pouches were tinctures of opium, and 1ml syringes and needles so that they could inject heroin whenever they needed. It wasn’t until 1910 when physicians in hospitals began to sound alarms about steep rises in overdoses, and not until 1924 when the manufacturing of heroin was outlawed. The term “junkie,” came from this period, where the addicted working class were forced to rely on criminal drug networks to keep their addiction at bay, and found money to fund this by collecting and selling scrap metal from junk yards. As the “respectable,” upper middle class addicts died out, the remaining working class addicts were reclassified as criminals - not patients.

It was around this time (1925 to be exact) that a psychiatrist called Lawrence Kolb published some dodgy research claiming working class addicts had personality defects that made their drug use different to the wealthy addicts being prescribed heroin by physicians. Kolb’s research set the scene for treating addiction as a criminal issue and not a health one. His studies were later disproven by mountains of evidence proving the addictive properties of opiates worked on virtually anybody exposed to them for extended periods of time - and Kolb admitted he had been wrong. But before this admission and disapproval of his research, Kolb established “narcotic farms” where opiate addicts were incarcerated and forced into unpaid labour, and experimented on by scientists and doctors. These farms were not closed down until the 1970’s when the ethical issues with using living, breathing humans as non consenting test subjects became too much of an ethical issue to ignore.

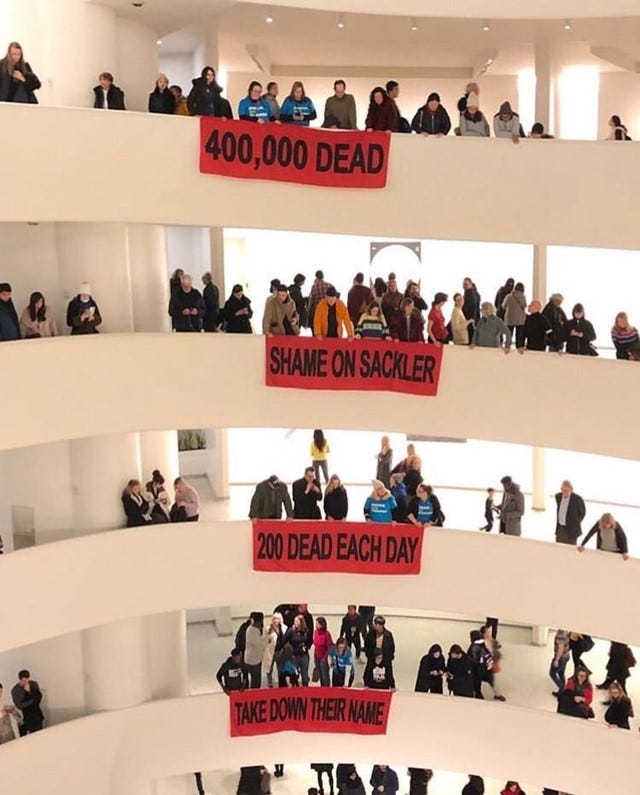

Between the 1930’s and the 1980’s opiate prescriptions were tightly controlled, and the addictive properties of opiates well known. To the point that many doctors opted for surgical procedures to alter nerve pathways over the prescribing of opiates. This changed in the 1990’s when Purdue Pharma, who were solely run and owned by a single family - the ultra wealth Sackler family, manufactured their new drug: Oxycontin. It was a cheap synthetic version of opium that had been around since the last opiate addiction epidemic, but they coated it in a time-release coating, cherry picked a piece of evidence that claimed that “less than 1% of opiate users get addicted” and began aggressively marketing it to the masses, skirting through the FDA approval process to get their drug approved for moderate and chronic pain, along with establishing campaigns to introduce “pain as the 5th vital sign.” There main point of persuasion: Oxycontin was a non-addictive alternative to morphine. Sounds familiar huh?

I don’t know if I can quite get across to a layperson how huge the doses of Oxycontin that Purdue was pushing general practitioners to prescribe was (and is) - 80mg tablets, three times daily, were the norm amongst many prescribers who were prescribing Oxy for joint pain, back pain, or menstrual pain. For context when we use oxycontin to manage post caesarean pain we tend to prescribe 10-20mg of oxycontin twice daily, with 5mg tablets of oxynorm (fast release oxycodone) hourly as needed - this means the absolute maximum dose would be 120 mg of fast release oxycodone, and 40mg of slow release oxycodone, most people will require much less opiate pain relief, if any at all. This means that for acute post surgical pain we are prescribing a maximum of 40mg of slow release oxycontin, while general practitioners in the US were prescribing up to 240mgs of that same drug, daily, for weeks on end, for joint and muscle pain. It was only due to pressure from the drug enforcement agency and addiction recovery groups that Purdue was forced to pull their 160mg tablet from the market - which would have seen doses upward of 320mg per day being prescribed for chronic, non severe pain.

What happened next was predictable, but apparently not predictable enough to stop. It turned out that the cherry picked piece of evidence about “less than 1% of addiction,” amongst opiate addicts, was actually a small observation of hospital data about inpatient opiate use - and wasn’t actually a study, nor was it applicable to long term outpatient opiate use. Purdue Pharma eventually faced (painfully inadequate) legal repercussions for misleading marketing, and their drug labeling had to be changed and included a black box warning - that is, a warning that their drug may result in death.

But in the wake of their marketing campaign that saw billions of dollars spent on drug reps pressuring doctors to prescribe more oxycontin, and receiving kickbacks for high levels of prescribing, the United States of America saw a wave of opiate addiction that put the post civil war era epidemic in its shadow. When patients ran out of their prescriptions they were hooked: they experienced the bone bending pain of dopesickness within hours from their last dose. If they couldn’t get their prescription refilled by their physician their next best option was heroin - drug cartels took note and began funneling heroin across borders and into communities to pick up where Oxycontin left off. The 1930’s narrative of addiction as a criminal issue had been bolstered by the Nixon era “War on Drugs,” in response to the crack epidemic 1970’s. Nixon declared drug use in the united states as “public enemy number one,” and President Reagan took this concept and ran with it: increasing punishment for nonviolent drug users - with caveats that kept the wealthy absolved by distinguishing the cheaper crack cocaine from the more expensive powder cocaine and the poor incarcerated with mandatory minimum sentences. In the mid 2010’s, both large suppliers and smaller user-dealers began lacing their heroin with fentanyl. Morphine is twice as strong as opium, heroin is twice as strong as morphine, and fentanyl is 100 times as strong as heroin. Fentanyl is synthetic, cheap, and gets you higher, faster, with less. By 2015 working class Americans were dying of addiction so frequently that the US saw it’s life expectancy begin to drop, opiate overdose became the leading cause of death for Americans under 50, and many states, like West Virginia were burying so many people from overdoses that they developed an indigent burial-assist programme - because their existing funeral and burial services couldn’t keep up with the demand. Graveyards that climb their way up the Appalachian mountain range, where mining towns were targeted in the early days of Oxycontin’s marketing, are stuffed full of headstones - many of them, teenagers, university students, and young parents, who all died from opiate overdoses.

In New Zealand the situation with opiates is far less sobering - thanks to a socialised healthcare model and our geographical distance from the rest of the world. However our affinity for addiction is equally as significant - and we get our drug of choice in supermarkets and corner stores and marketed and branded and sold to us the same way Purdue pharma marketed and sold OxyContin: almost 20% of people over 15 in New Zealand use alcohol in a way that is harmful. I also strongly believe that our illicit drug abuse statistics are being severely understated: after all, the statistics for some reason don’t include the people most likely to suffer abuse: those in insecure housing, or prison. How can our government claim that the rate of illicit drug abuse has remained “relatively stable at 1%” over the last 10 years while our prison population has risen and our rates of homelessness have skyrocketed in that time. New Zealand seems to have fallen for the rhetoric of the U.S. - that addiction is a criminal issue and not a health issue, and despite copious evidence that harm reduction approaches work best in preventing death and destruction in the wake of addiction, few people in government over the last 40 years have seemed to want to listen to this evidence. And as I write this, some of the first reports of fentanyl making its way into the cutting of party drugs within New Zealand are released by NZ media. New Zealand also has some of the most relaxed laws in the world about advertising drugs, in fact, the only country that has laws as relaxed as New Zealand’s about “direct to consumer advertising” of prescription drugs - is the United States. We are not as safe here as we think we are.

So that’s where we are: opium doing the thing it’s always done: reeling us in, hooking us on, spitting us out. Corporations doing what they’ve always done: pursuing financial gain at the cost of human lives. And governments doing what they’ve become most fond of: placing the wealthy elite ahead of the working poor, funneling money into police and prisons at the expense of healthcare and harm reduction. It’s chilling stuff to read, or contemplate for too long. For my next newsletter, please go gently. I want to tell you why I liked the book and the series Dopesick so much, despite the fact that it made me grapple with ghosts and stare down the barrel of a still smoking gun. Facts and policies and static recounts of history are helpful yes, but what about the people, the lives lived and lost? What about you and me and our dopamine desperate brains?

If you or a loved one are struggling, and need support, there are resources below:

If you are in crisis - If you’re concerned about your own or somebody you love’s immediate wellbeing, whether mental or physical, please dial 111/000/999/911 and ask for an AMBULANCE.

Most other services require you not to be under the influence of drugs or alcohol when you contact them (I know, I know, don’t get me started).

Drug and Alcohol Helpline - This service has multiple helplines depending on your needs, there is a Māori helpline, a Pasifika helpline, and a youth helpline

Community treatment options can be found here - Your GP is a great place to start to decide what options are best for you, they can refer you to funded services and help you navigate other free, and unfunded services.

Peer Group Support - 12 Step programmes may sound intimidating at first, but they will wrap you up in peer-based support and guide you to reaching out for further help

Alcoholics Anonymous: call 0800 229 6757 or email help@aa.org.nz

Narcotics Anonymous: call 0800 628 632 or email help@nzna.org

Further References

Black S, Casswell S. Recreational drug use in New Zealand. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1993;12(1):37-47. doi: 10.1080/09595239300185721. PMID: 16818311.

Brindley, P. G. (2019). Milk of Paradise: A History of Opium. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 129(6), e196.

Kolb, L. (1939). Drug addiction as a public health problem. The Scientific Monthly, 48(5), 391-400.

Macy, B. (2018). Dopesick: Dealers, doctors, and the drug company that addicted America. Little, Brown.

Measham, F., & Moore, K. (2008). The criminalisation of intoxication. ASBO Nation: The criminalisation of nuisance. Bristol: Policy, 273-88.

Norn S, Kruse PR, Kruse E. Opiumsvalmuen og morfin gennem tiderne [History of opium poppy and morphine]. Dan Medicinhist Arbog. 2005;33:171-84. Danish. PMID: 17152761.